The table is made of three pieces of fine-grained pine with 15 to 6 growth rings per cm, the wider grain confined to the outer edges. The wedge-shaped central strip was probably bent and joined to solid outer blocks, and the whole then carved in the usual way. The soundholes are C shaped and surrounded by a single line of 16black-white-black purfling. The double edge purfling is black-white-black, and the two lines cross over at the corners to form two points. Below the end of the fingerboard is a four-branched tulip motif inlaid in black-white-black purfling, with the ground within the design cross-hatched with a knife so the varnish collects in the cuts and darkens those parts of the design. An unhatched circle in the center of the design bears the stamp Barak Norman Londini Fecit.

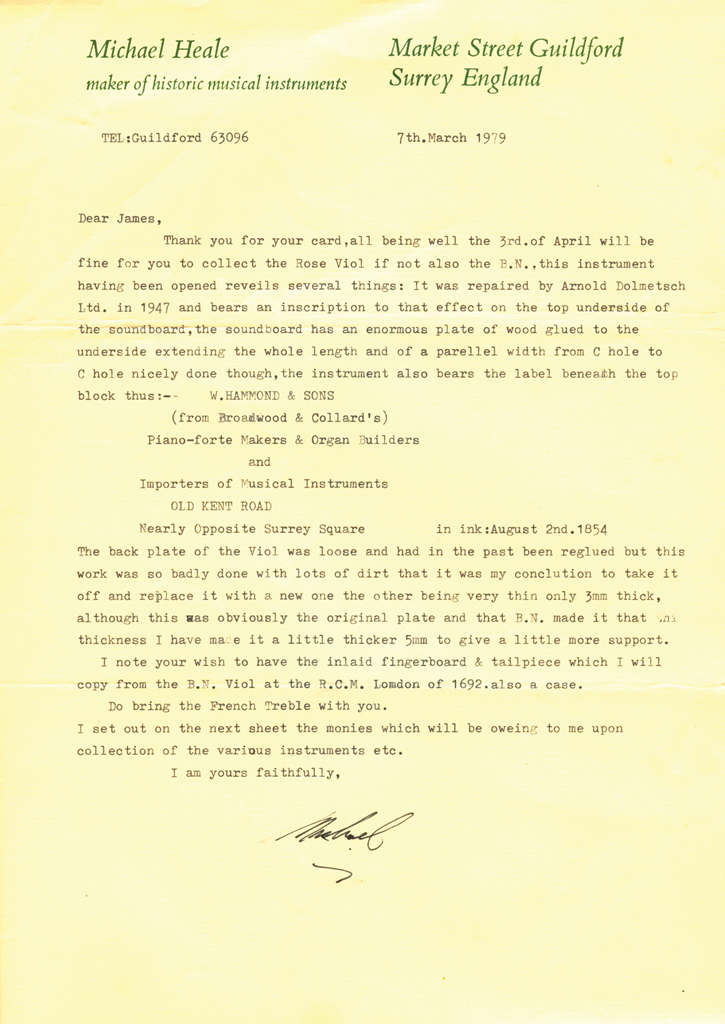

Extensive internal rebuilding was done in the Dolmetsch workshop in 1947.

The back is made of two pieces of English maple with medium flame angled slightly upward from the center joint. The double purfling crosses at the corners as on the table, and the inner line runs across the body above and below the fold, both lines turning down across the center joint to form a tulip. At the bottom block the two lines turn up to form a tulip of slightly different design. In the center of the back is the well-known purfled BN monogram. At the neck heel the purfling turns down to form two interlaced V’s, and a flower is carved between the V and the point of the heel.

The ribs are of straight, close flamed maple, with a border of double purfling framing a bold geometric design on each rib (cf. the 1600 Rose).

The neck appears to be pearwood and is surmounted by a composite pegbox consisting of an original Barak Norman back section, which carries an unusual downward trailing vine design, replacement cheeks with carving in the Norman style, and a separate antique head of a winged cherub, most likely not original. The boxwood pegs are by the Hills.

The modern marquetry fingerboard and tailpiece by Michael Heale are also in the style of Norman.

The varnish is a dark orange brown.

Body length 68.2

Body width

upper bout 30.6

center bout 23.0

lower bout 37.5

Rib height

top block 8.3

fold 12.3

upper corners 12.5

lower corners 12.6

bottom block 12.4

String length 69.5

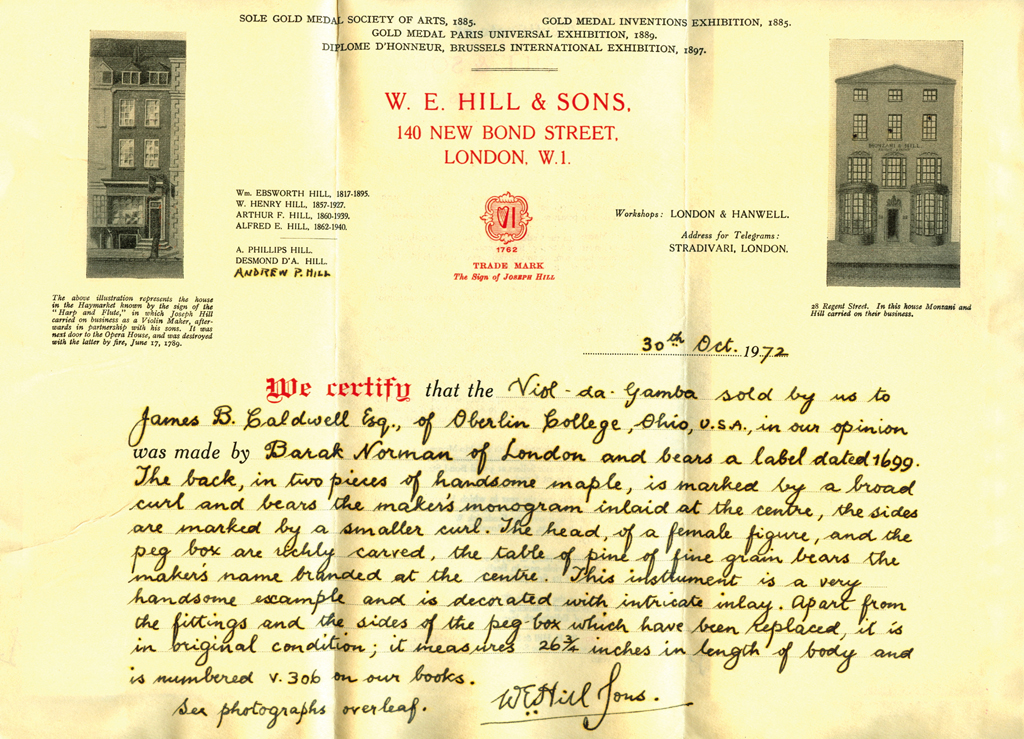

Labeled in ink

Barak Norman

At the Basse viol

in St. Paul’s Ally

London Fecit

1699