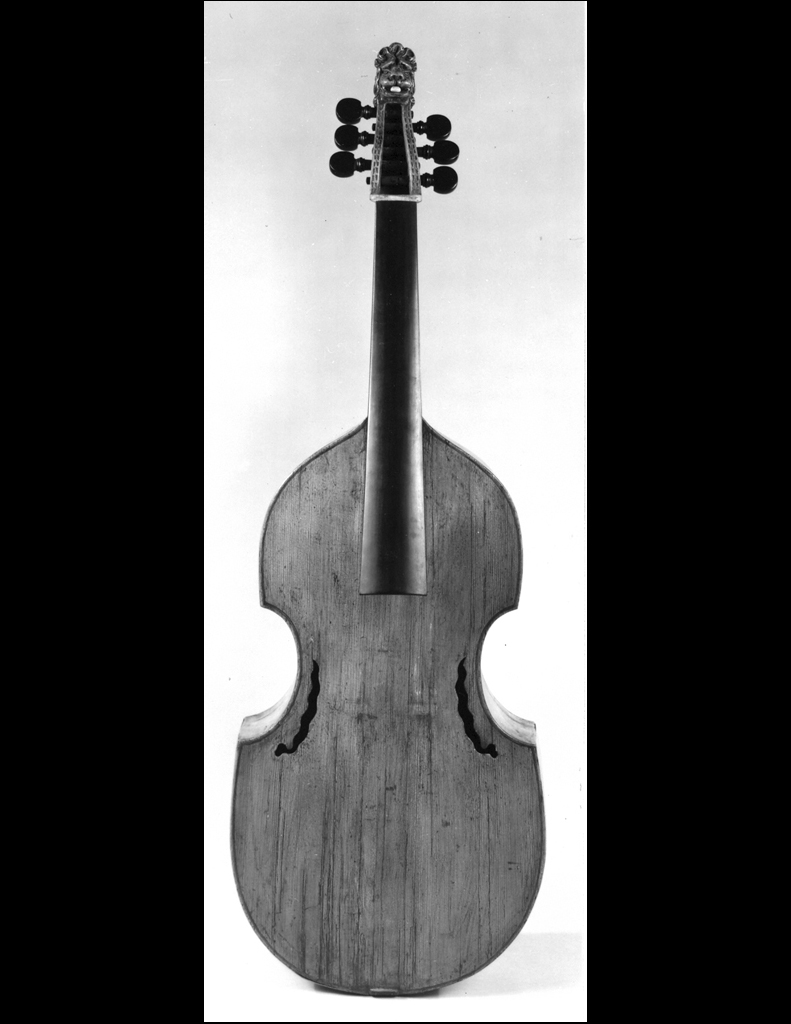

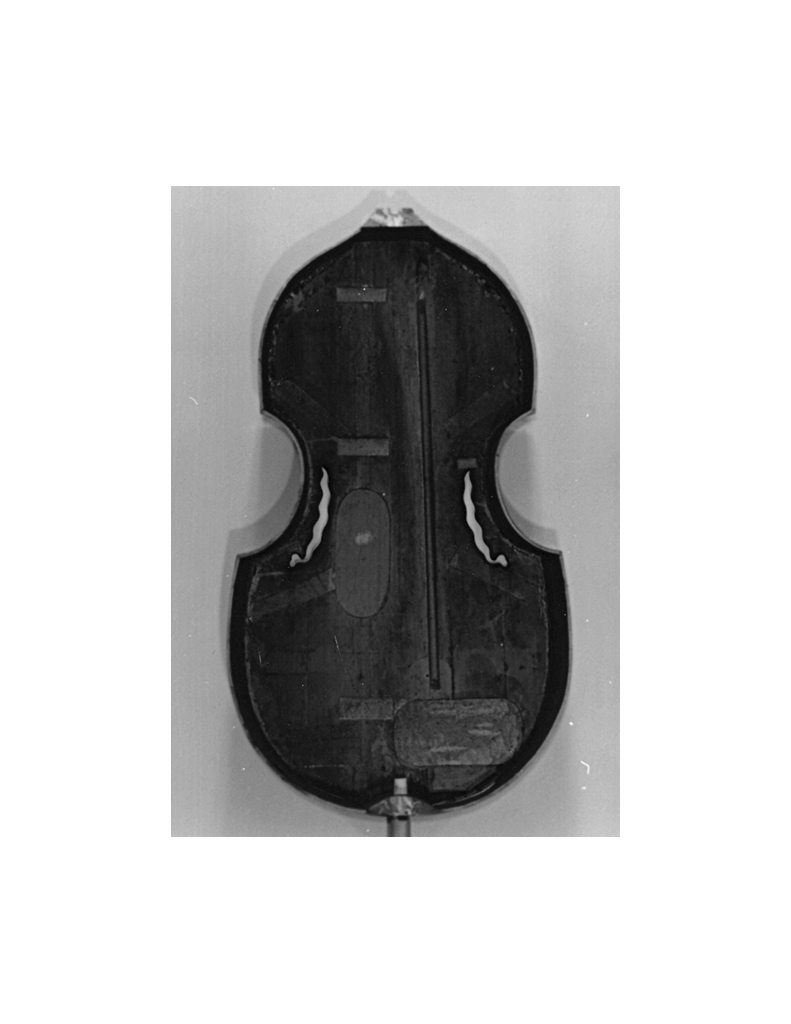

The table is of three pieces, with a wedge-shaped central strip that may have been bent and joined to solid outer portions. The soundholes are flame shaped. The edge purfling is a single band of black-white-black-white-black-white-black.

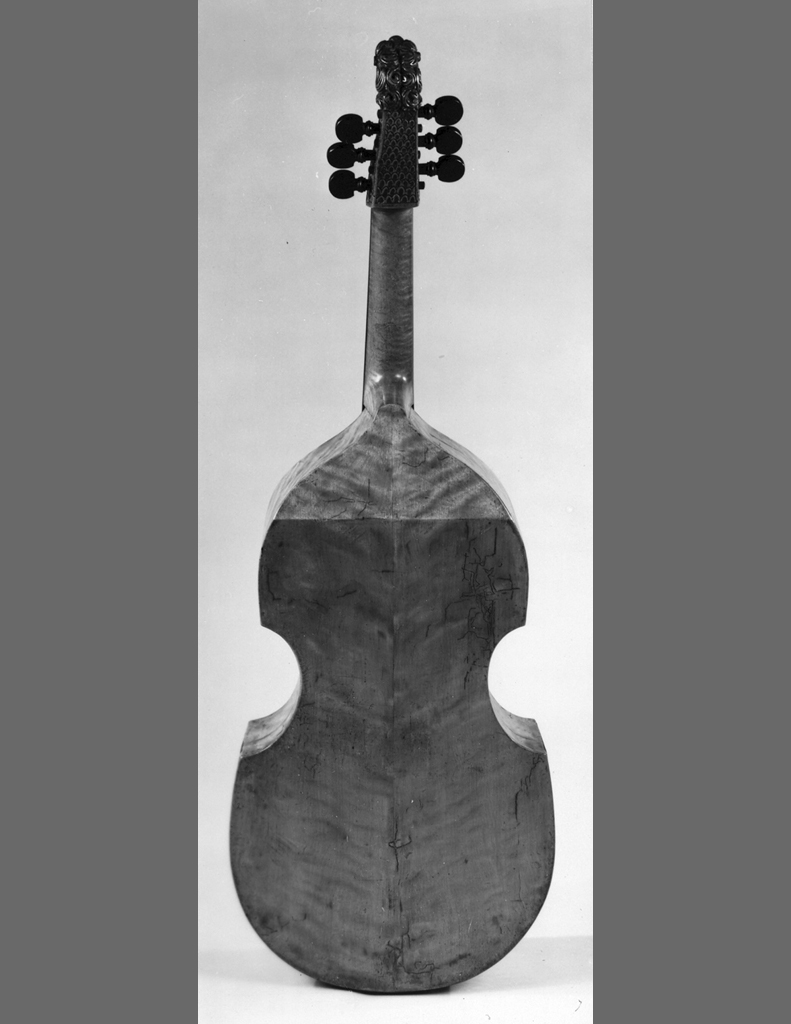

The back is two pieces of birch with a broad curl slanting slightly upwards from the center joint. There is no purfling.

The ribs are six pieces of similar wood.

The modern neck is maple, grafted to the original head and pegbox. The lion head sports an ivory tongue and teeth. The sides of the pegbox are carved with a vine motif, the back with scales, and the top of the cheeks with a double line of darts. The six modern pegs are ebony with bone pips.

The varnish is a pale golden brown.

Body length 70.0

Body width

upper bout 30.9

center bout 21.2

lower bout 36.9

String length 68.2

Rib height

top block 8.4

fold 12.2

upper corners 12.1

lower corners 12.0

bottom block 12.4

Label

Gregorius Karpp ca. 1700

Restoriert 2003 Ingo Muthesius

[modern]

Bought in January 1973 from Tony Bingham, London