The right to be an author?

But I would like to highlight another, and more hypothetical point. Beyond the implications that the liturgical regime in which he wrote has for the status of his works, and the paradoxes of our way of listening to them today,9 the very fact of being an author in a pre-copyright age posed a problem for Bach. “SDG” (Soli Deo gloria, “to the glory of God alone”), he writes at the bottom of most of his scores. This expresses so well the idea that we have of him that it serves as the title for many biographical or popular works devoted to Bach. Invariably, this inscription is remarked upon as though it were a dedication: Bach offers his work to God. This troubles neither our image of him, nor our perception of the music. The grandeur of his art is only reinforced by the fact that he is a man who is so religious, so far from worldly celebrations and earthly honors, that he only composes for the greater glory of God, ad majorem Dei gloriam. Even if this is assuredly true, it is not at all what Bach is saying. “To God alone be the glory” is an entirely different, and equally profound idea. Not “I celebrate the glory of God through my works,” but “the merit of my works belongs to God alone.” And He is not worried about copyright! But the “author-function” (Foucault 1969) that Bach occupies in our modern world prevents us once again from understanding, this time on the theological front. It is for this reason that I find the slide in meaning, and the incomprehension that it demonstrates, highly significant: it bears directly on the question of the author. The only creator is God, Bach reminds us at the end of each of his works. When asked of his calling, he answered “theologian.” In a similar vein, how else would an African or American Indian officiant answer, surprised to be promoted to musician after being recorded by an ethnomusicologist?10 The paradox of the creator is our invention, we moderns, we Westerners, not theirs.11 The evidence that makes authorial rights into a financial and judicial subject, seeking recognition of ownership by a creator with respect to his work, is precisely its most problematic trait. But our theory of creation has already been constructed, and within it we are deaf to evidence of Bach. We have annexed him on the one hand, while on the other, it costs us nothing to send back to the anthropological richness of their premusical alterity all the collective modes of creation from traditional or ethnic societies that stand in counterpoint to us.12

Now, I believe that this essential debate—do I have the right to create? Is it I who create?—is one that Bach had with himself. After having struggled his whole life against the narrow conception of the role of music in the Pietist liturgy by defending the idea that the more music is beautiful, powerful and moving, the more it serves God, he pushes his conception to the limits with the St. Matthew Passion. And the questions are not at all musical: How to show the solid choice of the people in favor of Barrabas? The betrayal by Saint Peter? The tortures inflicted on Christ? His suffering, when he asks if he has been abandoned? The crucifixion and death of the Son of God? The challenge is entirely theological. It questions the sense and function of aesthetics, and in particular the power of music and spectacle. Bach sees his musical art as a unique medium for making listeners feel once more, feel anew, with the necessary intensity, the violence of the Passion, which ordinary ritual has covered over with tranquillizing familiarity. He writes music that is dense, shocking, extended, with dissonant, unprepared intervals that underline the most dramatic moments in the text. He makes a double choir bark to show the hatred of the mob; he makes the heartbreaking accents of the viol groan at length to speak of despair.

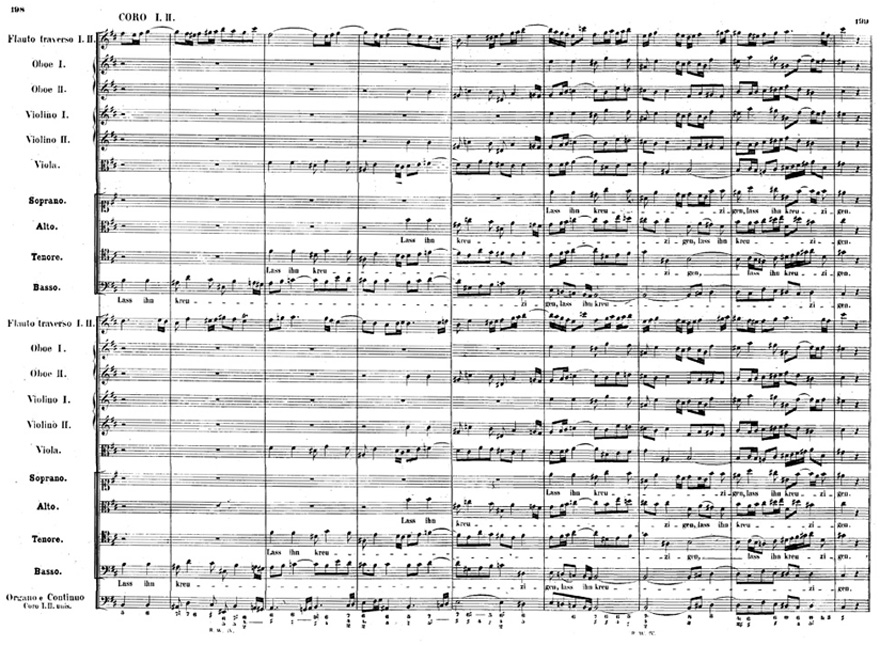

Score of "Laß ihn kreuzigen," Bach-Ausgabe…

“My God, we are at the opera!” a bourgeoise would have exclaimed, ready to faint. Romantic historiography, frustrated by a Bach biography otherwise so poorly supplied with heroic events, jumped on the opportunity to interpret the underlying meaning and motivation. Hidebound Leipzig burghers, an audience that does not understand the power of the work, blind and fearful burgermeisters who demand that he return to his place, administrative pettiness that silences the genius…nothing is lacking for the portrait of the suffering artist.

But such a tale says much more about us than it does about Bach. As a continuation of the analysis of the event that Denis Laborde (1992) proposed as inverted blasphemy, both in the text (it is the Jews who blaspheme in accusing Christ of blasphemy), and in its setting in the Passion by Bach (the violence that the audience refuses is not the violence of the music, but that of the text, that music makes us see), we can imagine an entirely different version of the drama played out in Leipzig between 1727 and 1730.13 Bach dies in 1750. Between the St. Matthew Passion and his death, more than twenty years pass, during which he, the musician-theologian, writes nary a single religious work, unless it be…a Catholic Mass, the Mass in B minor! Instead, he sets in motion the didactic works and the formal challenges that will assure him a place in the musical pantheon. Really, was it the burgers of St. Thomas who had such power over his “career”? Was it they who managed to turn a passionate theologian into a modern composer? We should thank them! –though it is a lot to grant them. This is certainly the version suggested by Alberto Basso, author of the 2,000-page bible on Bach published in two volumes by Fayard (1985). During this period, the list of religious works by Bach, “little by little worn down by incessant conflicts with both religious and civil authorities” (vol. II: back cover), becomes thinner. Although it is never so clearly enunciated, a careful reading reveals that apart from a handful of cantatas, Bach composed, ex novo, no more music for the church.14 In comparison to the earlier flood of sacred music, Basso simply notes, with indulgence, that these works become “intermittent and exceptional” (ibid.: 445). He has just “excused” the great master, whose “extraordinary power of creation, which had led to the birth of the incomparable series of cantatas of the years 1723-1728, might legitimately have weakened somewhat” (ibid. : 480). Considering the series of works that follow during the last twenty years of Bach’s life, which Basso himself includes among “the most audacious” that have ever been written, one wonders if excusing him is quite the right thing, and if it would not be preferable to have a different understanding of the “severe and highly technical” change of direction (ibid.: 468) taken by the cantor.