Though much remains unclear about the life of John Rose, we do at least know that there were two instrument makers by that name, father and son, working in Elizabethan England. Sir Thomas Chaloner’s account book records several payments in 1552 “to Jo: Rose for an other vyall ... of the finest sort” and for repairing lutes and supplying strings. Nine years later a lease granted the tenancy of several rooms in a former royal residence in London called Bridewell to “John Rose together with Jone his wife,” explaining that “the said Rose hathe a most notable gift given of God in the making of instruments even soche a gift as his fame is sped thorough a great part of Christendom....”

The 1615 edition of John Stow’s The Annales of England reported that “In the fourth yeere of Queene Elizabeth [i.e., 1562], Iohn Rose, dwelling in Bridewell, devised and made, an Instrument, with wyer strings, commonly called Bandora, and left a sonne farre excelling himselfe, in making Bandores, Voyall de Gamboes, and other Instruments.” As John Pringle points out in his article “John Rose, the founder of English viol-making” (“John Rose, The Founder of English Viol-Making.” Early Music 6 (1978): 501–11), it is unclear from this statement whether Rose not only invented the bandora in 1562 but also died in that year. Though documentation is lacking, such a conclusion is plausible considering that by this time he had achieved international fame and is thus likely to have been born some three or four decades earlier, perhaps around 1525. In that case, the “Jhon Rosse Instromentmaker” who was buried on July 29, 1611, in the parish of St. Bride must have been his son, because by then the father would have been about 85 years old, an extraordinary age in those days even if the composer William Byrd was in that very year still actively publishing music in his early seventies, more than a decade away from his own death in 1623.

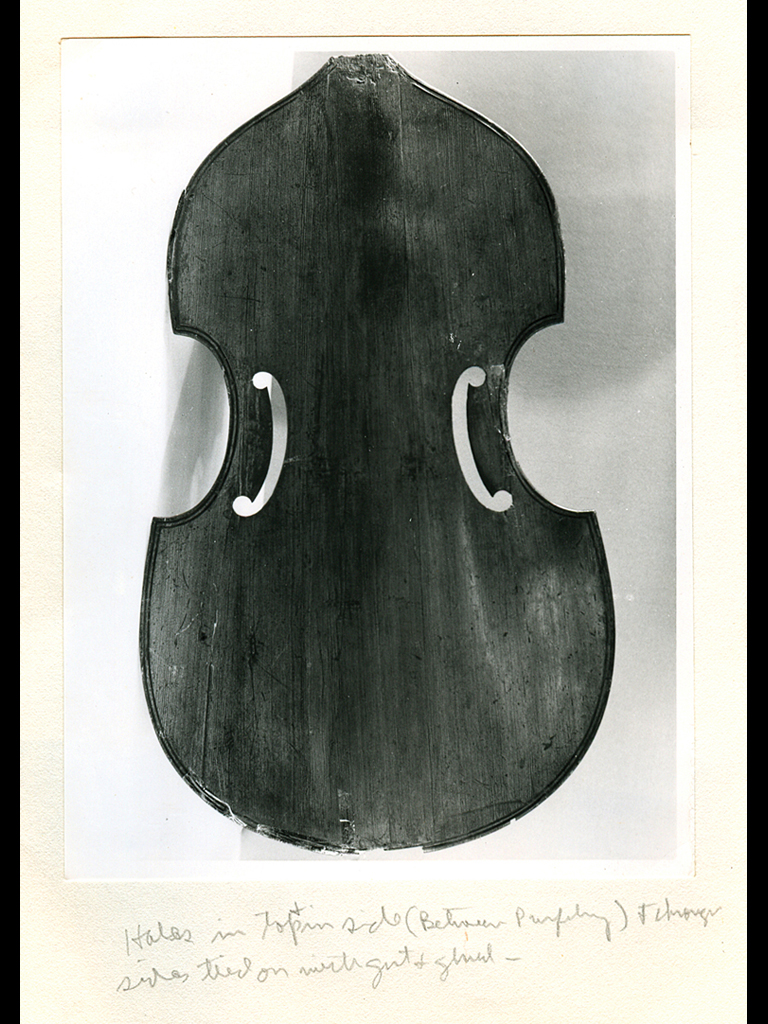

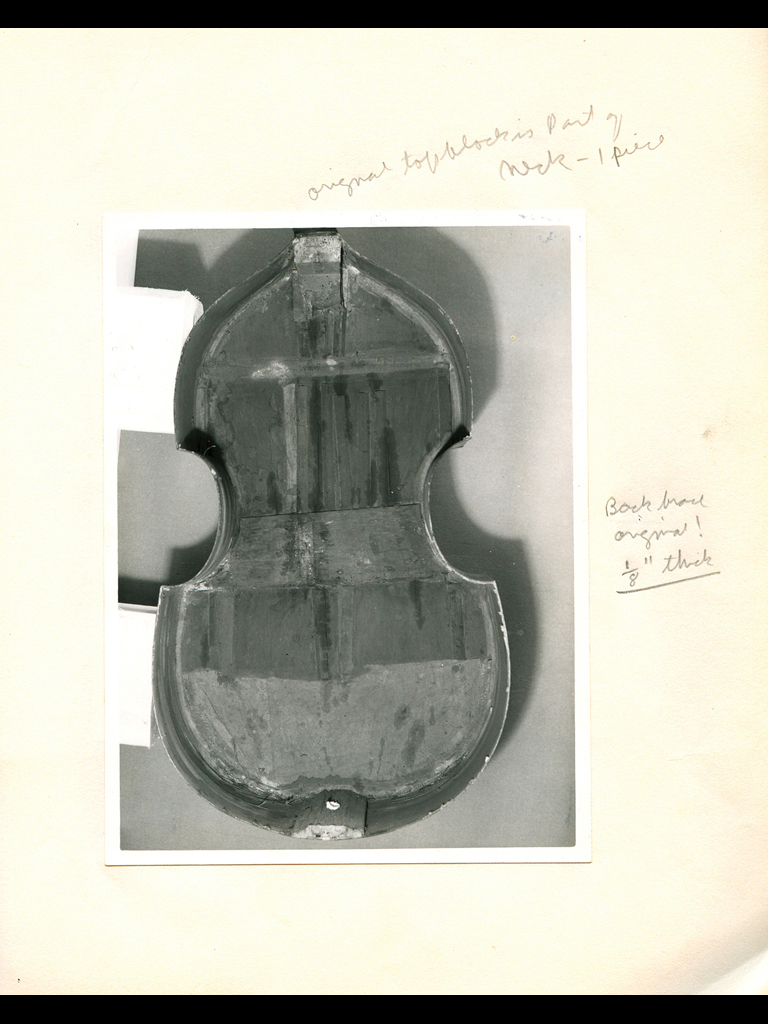

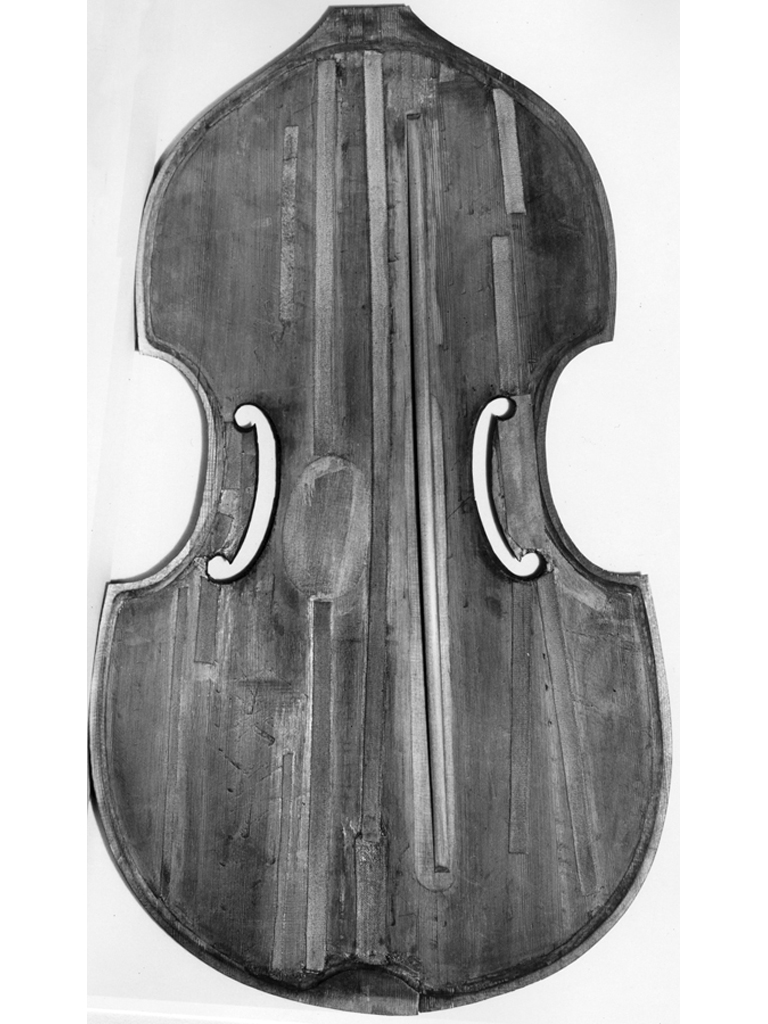

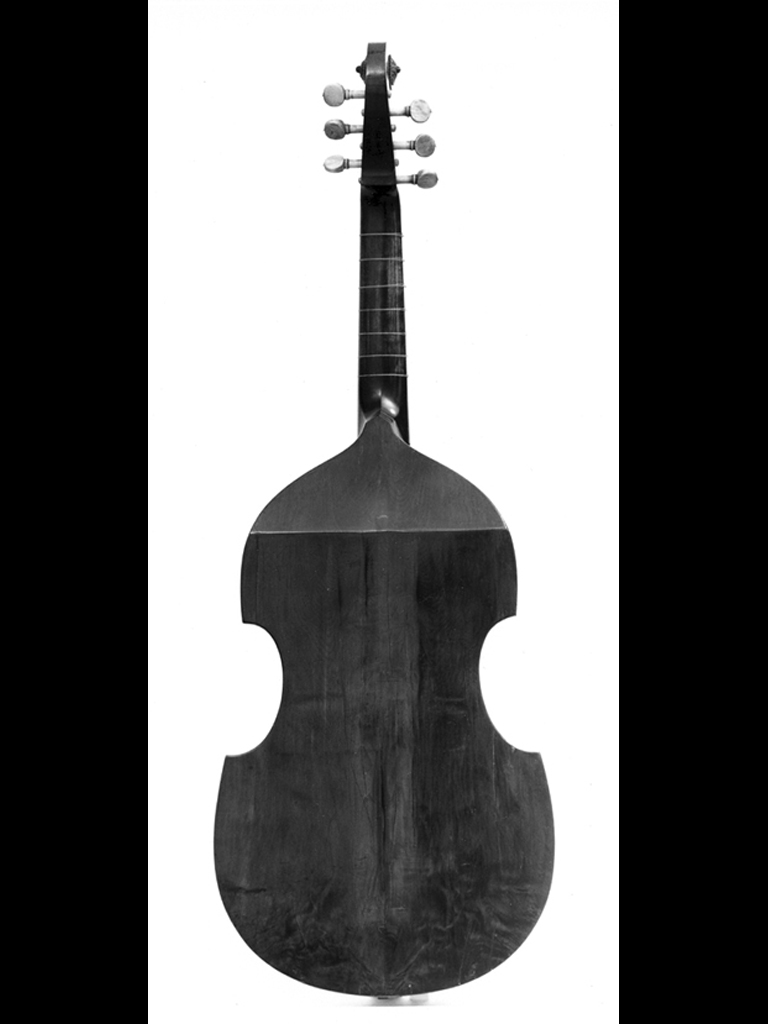

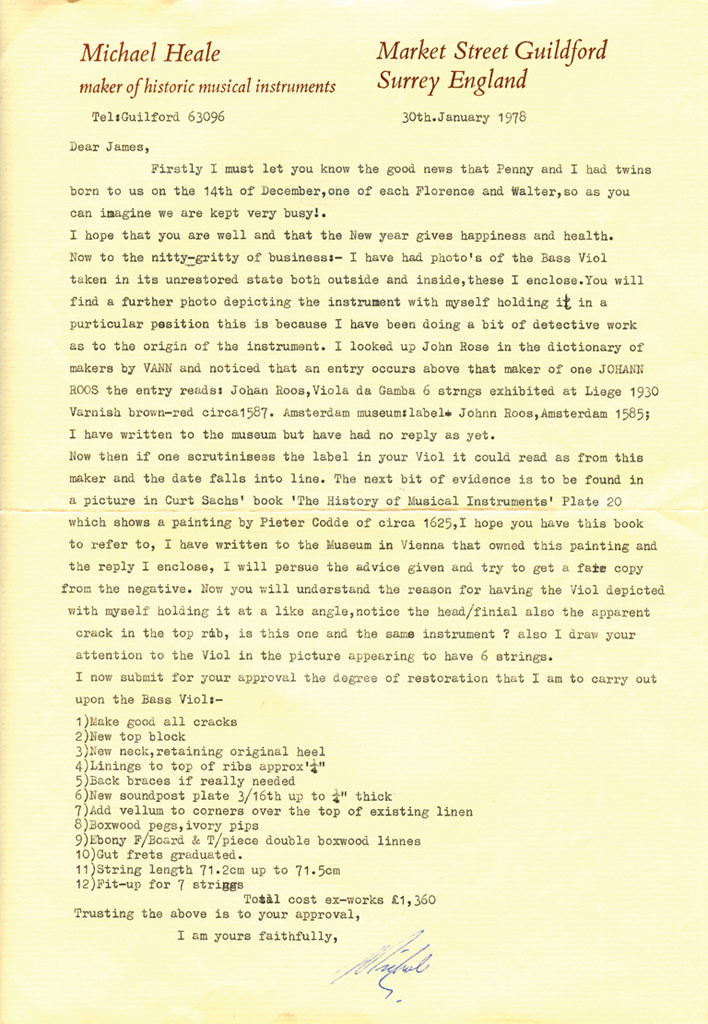

Most likely all surviving viols signed by or attributed to Rose were made by the son, with the possible exception of the bass at the Victoria and Albert Museum. When this was purchased in 1877 the auction catalogue assigned it a date of 1560, but that was only a guess (perhaps based on knowledge of Stow’s report), since the label reads simply “John Rose.” On the other hand, Pringle notes that the irregularly figured wood of its back and ribs is quite similar to that found on the tenor (or lyra) viol in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, which is labeled “John Rose 1598”; assuming the V&A bass was made around the same time, it too would probably have been built by the son. (The museum currently lists it as “ca. 1600.”)

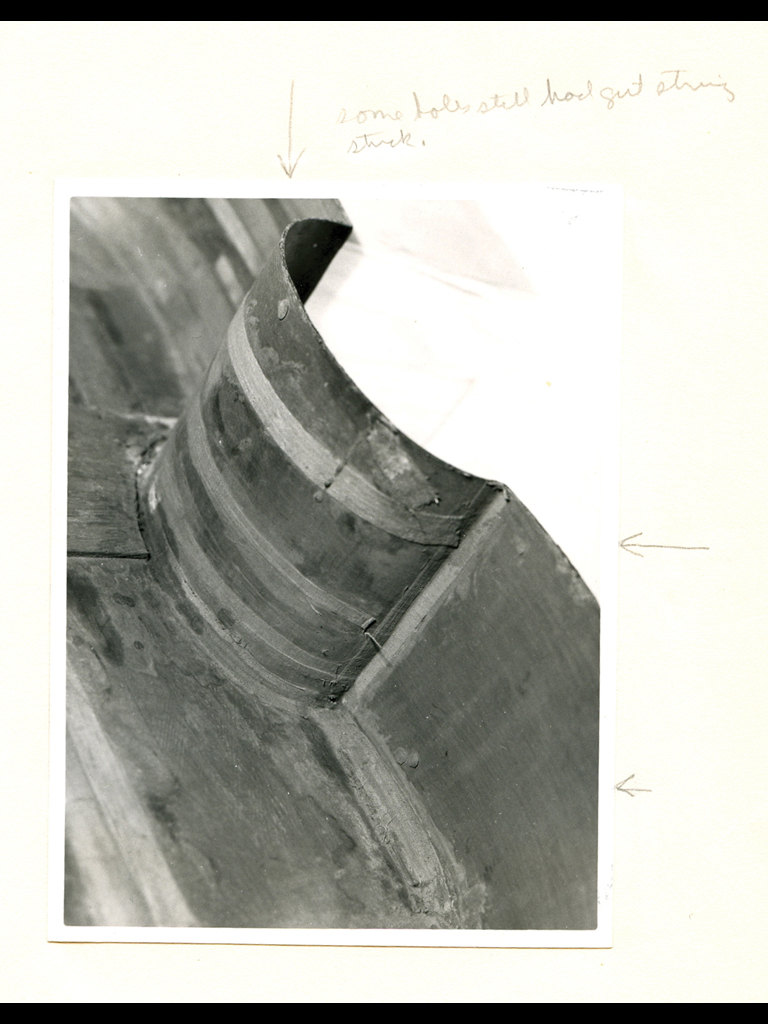

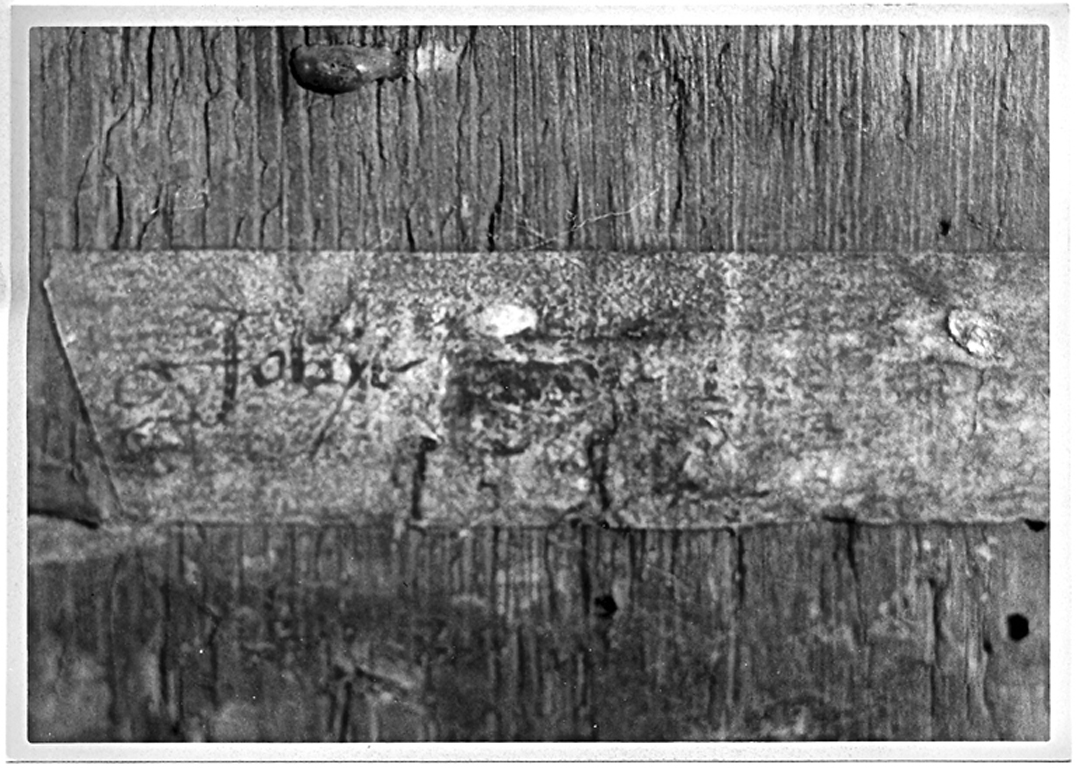

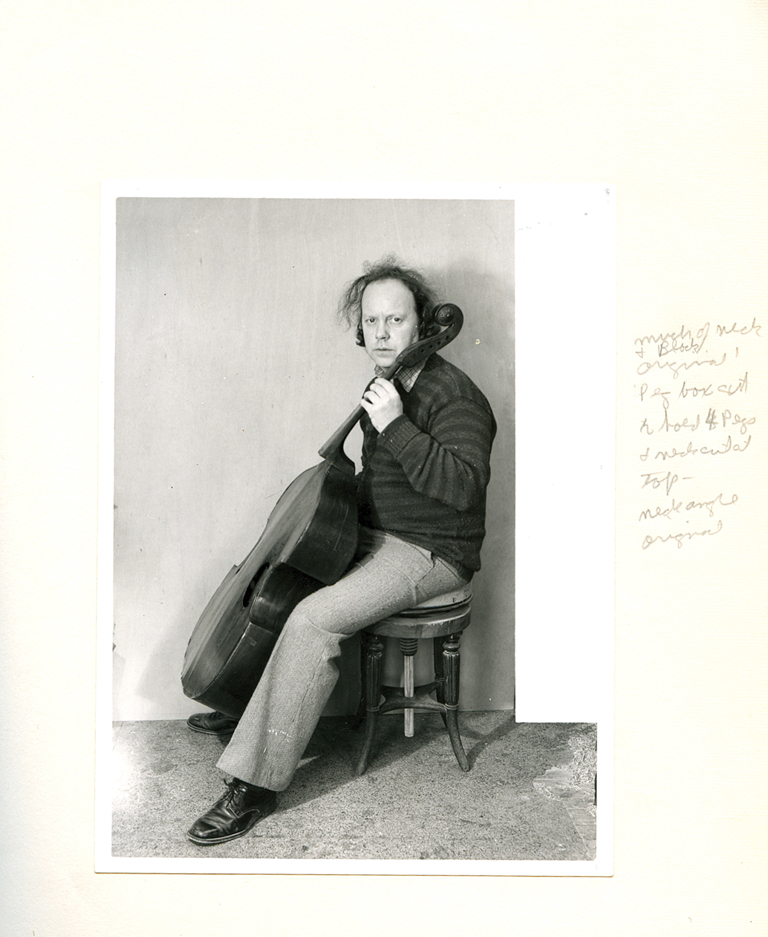

The label in the Caldwell Collection’s 1584 bass is nearly illegible, with the date being the clearest element of its text, placed alone in center of the second line. Above and to the left, in a handwriting that may or may not be the same, appears a name that is almost certainly “John,” even though its last letter has been damaged. Following this is a short word whose first letter seems to begin with a vertical stroke and thus could well be an R, though what follows is indecipherable. On the rest of the first line no marks at all can be seen, but surely this was not originally left blank, and there is enough space to have accommodated the words “in Bridwell,” a phrase Rose is known to have used on other labels.Although significant differences in body outline, soundhole placement, and decoration exist between this instrument and the Victoria and Albert Museum’s example, there are so few other viols securely attributed to Rose that it is difficult to know how widely his designs may have varied. If it was indeed made by Rose, it would be his earliest extant and dated viol. In any case, it seems that he made two very different types of body outlines, as demonstrated by the festoon-shaped bass in the Caldwell Collection and the similar instrument in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Both are unlabeled but have been attributed to Rose in large part because their lavish decoration reveals the work of a specialist master craftsman, a role in which he had no known competitors in late-16th-century England.

Other basses that have been associated with Rose’s name include one owned by the late Dietrich Kessler that might actually have been made by the slightly later Henry Smith (whom Thomas Mace mentioned alongside Rose in the often-cited list of the best old viol makers that he published in 1676); a much-altered composite at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York whose decoration is similar to that of the two festooned basses previously mentioned; and a third, labeled “John Ross 1609,” that has not been seen since an exhibition in England in 1951. There is also a second tenor (dated 1604) at the Musée de la musique in Paris and an unlabeled treble (currently necked and strung as a small tenor) at Hart House in Toronto, whose carved head is a near-twin to the one now mounted on the Caldwell Collection’s festooned bass.