Soli Deo Gloria

Was Bach a Composer?

Antoine Hennion

Ave Maria, Charles Gounod, Roberto Alagna tenor, Chorus and Orchestre national du Capitole de Toulouse, Michel Plasson music director, EMI Music France 1996.

/ 01:03Ave Maria, Charles Gounod, Roberto Alagna tenor, Chorus and Orchestre national du Capitole de Toulouse, Michel Plasson music director, EMI Music France 1996..

/This is the Ave Maria by. . . whom, after all? By Bach, by Gounod, by Bach, Gounod-Bach, by Bach-Gounod? To whom do we pay the royalties? The author of this music has varied over time, for reasons that have less to do with attribution than with current copyright law, under which music is produced and given value according to the chain of creation-work-performer-distributor-public. As it happens, Roberto Alagna, star tenor and occasional practitioner of crossover, sings the melody that Charles Gounod superimposed on the first prelude of The Well-Tempered Clavier by Johann Sebastian Bach, written entirely in arpeggiated chords.1 The cultivated amateur may smile at this, either with disdain or amusement. No doubt the exploitation of this classic by the modern record industry continues the practice of romantic tampering with early scores by unscrupulous musicians of the nineteenth century. Happily, there are serious musicologists and performers who have been able to render to Bach what Bach is owed: authority over his music. They do the double work of policing, on the one hand attributing the music that is by him, and on the other playing this music in a way that is faithful to his intentions, as much as we are able to conjecture. Therein lies the heart of the problem of “intellectual property” à la française: to reward the creator and to respect his moral rights with respect to his work. And yet. . . let us listen to the second selection, following along with the score.

First page of the score: Passacaglia in C minor, manuscript copy of the lost autograph, about 1720-39, Germany, Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Mendelssohn-Archiv, MusmsBachP274, page 31 © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN Image BPK.

Audio: Johann Sebastian Bach, Passacaglia in C minor, BWV 582 ; Marie-Claire Alain, organ. Erato Disques, 2005.

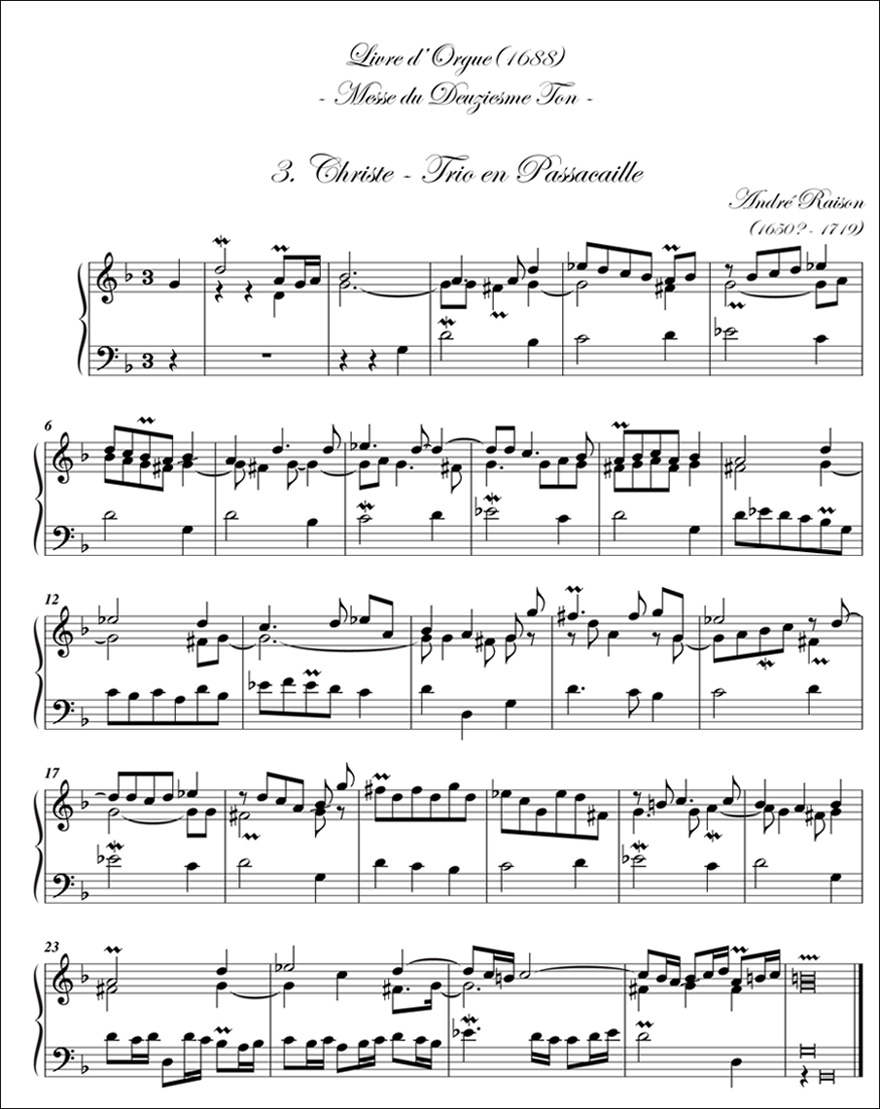

The music is certainly by Bach, the Passacaglia in C minor for organ,2 one of his best-known works. The score presents the theme in the bass line (transposed to G minor). But this is not by Bach: the score is that of the “Christe” of the Mass in the second mode of the Premier Livre d’Orgue by André Raison, dating from 1688.

André Raison, Livre d'Orgue (1688), Messe du Deuxième Ton © Les Éditions Outremontaises, 2008.

Audio: youtu.be_K6fcr44AARQ.ogg

The “rewritten” music is that by Bach, beginning from an original taken note for note from the French organist. This is not an isolated case for Bach. From the Gigue by Gaspard Le Roux that one discovers in the first English Suite (unless both Bach and Le Roux borrowed it from Charles Dieupart) to the Stabat Mater by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, which became the motet “Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden,” on to the organ concertos taken from Antonio Vivaldi, Bach never stopped borrowing his music from others.3 One conspiracy theorist recently created a web site to denounce the complicit elitism of artists and the bourgeoisie, who, after two-and-a-half centuries, have entirely fabricated the glory of a composer, little known during his lifetime, who did not even create his own music, in order to prevent the success of true musicians who are both classical and popular, such as Vivaldi.4 But by accusing Bach of being a plagiarist, the author does nothing more than apply the same model of authority that we have just mobilized, in the case of the Ave Maria, to protect him against his own plagiarists. In both cases, we must be aware of the anachronicity of this model.

The debate regarding authors’ rights has recently gained importance among ethnomusicologists. Paradoxically, if one considers how far from this kind of judicial and modern formulation is the style of music production that interests them, they are now constantly faced with this “modern” problem on their terrain: ethnomusicologists assign copyrights to present-day performers of ethnic musics that had from time immorial been performed without any “authors.” The case is enlightening, if we compare it to the one we face in the case of Bach. But it does not lead at all to the usual comparison between traditional and classical music, contrasting a collective, anonymous mode of production against our modern one governed by the “authorship” regime. On the contrary, the ethnomusicologists’ problem will help us to better understand our own position: ethnomusicologists are forced to treat as belonging to our modern world musics produced under another regime—so do we, regarding Bach. What ethnomusicologists confront at a spatial level, we precisely confront at a temporal one. By definition, non-classical music is endlessly varied and repeated; transmitted orally; connected to sociocultural codes and difficult to separate from the rituals or ceremonies where it is played, or from the dance or words with which it is associated; these musics are perverted by the very fact of calling it music, and the modern concept of an encounter between performers and an audience describes them quite poorly. In contrast, the classical composer is characterized by opposite peculiarities: a name equal to his status; a solidly established catalogue of written works, studied in detail by generations of musicians; a reverential succession of scrupulous performers; a material presence in the form of recordings neatly cataloged and criticized by scholars; a clearly-defined place in a social geography of highly differentiated tastes; and, as both cause and effect of this rich configuration, the very evidence of belonging to a universe, music, which has acquired autonomy.

Stills from the film Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach, by Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, 1967, starring the organist and harpsichordist Gustav Leonhard as J.S. Bach. With permission of Éditions Montparnasse.

» Swipe for more pictures.